Into the Bookshop

The vast majority of the fragments to be found in bindings in the Harsnett collection are from medieval manuscripts discarded in the sixteenth century. There are, however, a few which are more ‘modern’ and two sets are suggestive of the activities of the bookshop and the bindery.

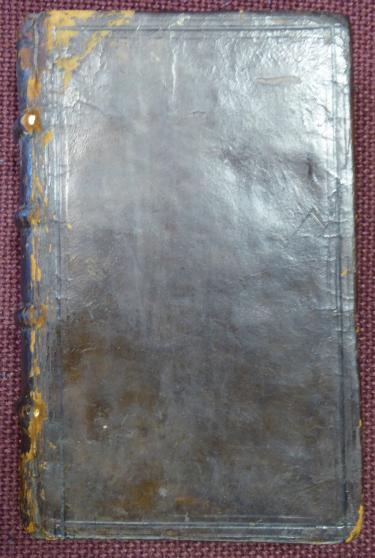

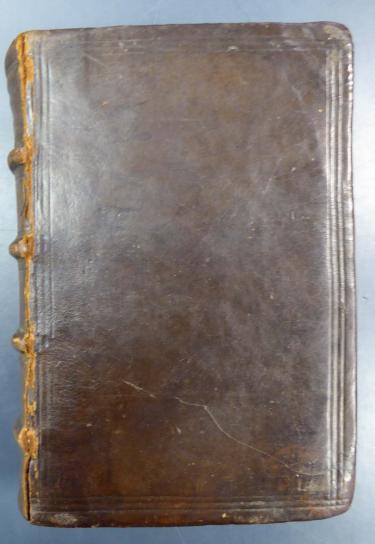

Two of the smaller volumes, both dating from the early 1590s, are bound in a similar style of plain calf over pasteboards. The only pattern is provided by fillets at the edge of each board; the endbands are not of the same design on both volumes but, in other elements, they would seem to be closely related. They also share the use of paper flyleaves which reuse recent documents which had clearly outlived their usual lives. What is more, both of the documents are related to book-selling activities.

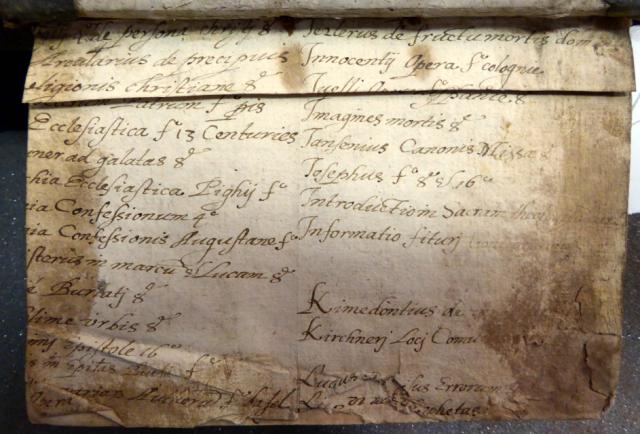

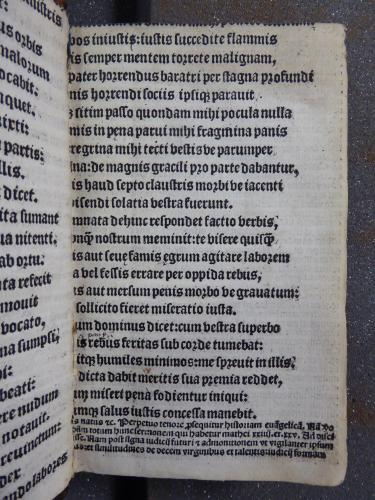

Of these two documents, only one has been designated a Babel manuscript number, since the other survives in a single fragment. Babel MS 27 consists of two sheets from what would have been a more extensive list of books. They are arranged alphabetically by author and are mainly theological; the only dates recorded are 1594 and 1595, presumably to alert the recipient of the list to the latest publications. In other words, we can date this to 1595 or 1596. It is also clear that this was written on the continent and was presumably sent to London, for a book-seller to decide which of the volumes to purchase.

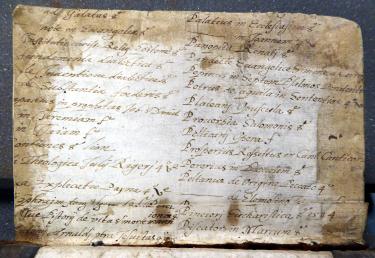

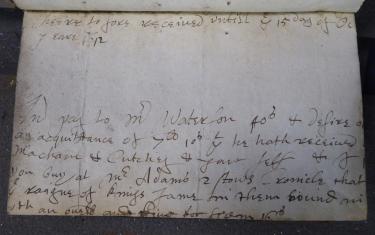

The other document comes from a few year’s later. It is unusual among the fragments in the Harsnett collection for being in English. The text is partial but what remains is a record of a transaction concerning volumes of John Stow’s Chronicles. It refers to it containing sections on the reign of James I and mentions a ‘Mr Adams’, assuming this is the publisher, Thomas Adams (d. 1620), the edition must be either that of 1605 [STC 23337] or 1615 [STC 23338]. The earlier date is perhaps more likely, since the note of the transaction was considered obsolete by the time a volume published in 1611 came to be bound. The record also mentions the volumes being bound and we might wonder whether the intended binder was the person who also then cut up this record to use it within the book that now sits in the Harsnett collection.

These fragments stand apart from the majority described in this pilot project: they are on paper, and they are from ‘modern’ documentary texts. They reflect changing practices: in earlier generations, parchment from medieval manuscripts was in plentiful supply. While there is ample evidence that some were still available to be turned into fragments at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the quantity in circulation had surely decreased. Substitutes, therefore, were sought. Some binders continued the habit of using printed waste in binding - and the person at work on these volumes did just that: in the volume in which the transaction concerning Stow's Chronicle sits the other flyleaf is from a printed volume. In addition, though, this binder turned to what we might call his waste-paper basket, fishing out old documents that had outlived their documentary use so they too could be recycled.