Drawing a blank

It is the working practice of early modern binders that furnish the evidence for the pilot project of Lost Manuscripts. Some binders – but by no means all – thought it appropriate when putting covers on a book to destroy another book in the process. They would use strips or leaves or bifolia from manuscripts to strengthen the binding or to adorn the inside of the boards. The result was usually that handwriting from a previous century was on display in the binding to be seen by whoever came to own the volume. But this was not universal practice.

A few binders, it would seem, appreciated the advantages of employing parchment in their handiwork but avoided, as far as possible, using pieces where text was present. One such case comes from the shop of Thomas Thomas, who was printer to the University of Cambridge from 1583 until his death in 1588. Thomas, a Londoner, educated at Eton and at King's College, Cambridge was known for his Puritan views. As well as being a printer, he ran a bindery, inherited from his wife's first husband, who was John Sheres (d. 1581).

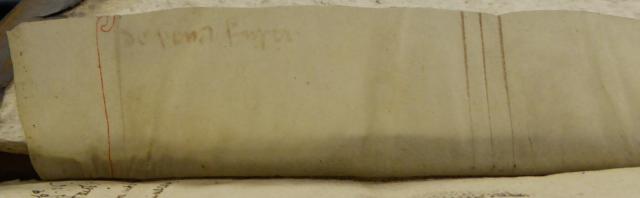

In this volume, there are two broad strips of parchment, both of which are nearly pristine. We would not know these came from an earlier manuscript if it were not for the signs of ruling on them and for the interventions of a reader of the now-lost text, writing in plummet. The notes have faded but we can reconstruct enough to surmise that we have sections of bottom margins to a legal text.

It is worth dwelling on the implications of these fragments. On one level, Thomas Thomas’s practice might seem to us more understandable to us than that of binders who allowed pastedowns with text to be on display: did those binders expect their customers to enjoy the presence of those remnants of earlier books or did they assume that they would, in effect, be blind to them? The latter possibility would seem unlikely since others, like Thomas, went to the trouble of excluding text when they could: we might sense that he, like us, would have considered the presence of a fragmentary text to be intrusive. There is, though, another consequence of what he was doing which we are liable to find surprising or even disconcerting: he would take a bifolium, cut off what surrounded the text – and then discard the central element. For him, what had been marginal was all that was useful. Perhaps for this Puritan, there was a virtue in retaining only the blank parts of manuscripts whose words might smell of old religion. In his bindery, it was precisely the spaces of the page which were most likely to be recycled, and the text the least likely to survive.